Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes

Diabetes is characterised by chronic hyperglycaemia caused by increased insulin resistance or reduced insulin release.

Aeitiology:

Diabetes may be primary or secondary. The main types of diabetes include type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes, secondary diabetes, and gestational diabetes. This post mainly discusses type 1 and type 2 diabetes. The main differences between type 1 and type 2 diabetes are summarised below:

Type 1 diabetes

|

Type 2 diabetes

|

Caused

by the autoimmune destruction of B

cells in the islet of Langerhans.

|

Caused

by increased peripheral insulin

resistance and reduced insulin

secretion.

|

Tends

to present before puberty, but may present

at any age.

|

Tends

to occur in patients above 40 but increasingly affects younger individuals.

|

Polygenetic,

associated with inheritance of HLA types: HLA-DR3 and HLA-DR4. Associated

with other autoimmune conditions.

|

Polygenetic

with high twin concordance (80%) but triggered by lifestyle factors.

|

More

common in Europe

|

More

common everywhere, especially in Africans and Asians.

|

Presents

as polydipsia, polyuria, weight loss, and ketosis. May cause diabetic

ketoacidosis (DKA)

|

Often

presents asymptomatically, may present with complications (eg. Cardiovascular

disease) and may cause non-ketotic hyperosmolar state. Rarely causes DKAs.

|

Latent

autoimmune diabetes of adults (LADA) refers to a type of type 1 DM which

occurs in older individuals with slower progression.

|

Maturity

onset diabetes of the young is a rare autosomnal dominant form of type 2

diabetes affecting young people with a family history.

|

Causes of secondary diabetes include:

- Damage to pancreas: Surgery (total pancreatectomy), chronic pancreatitis, haemochromotosis, cystic fibrosis.

- Endocrine causes: cushinings syndrome, acromegaly, pheochromocytoma.

- Drugs: Steroids (antagonises insulin), Thiazide diuretics, Antiretrovirals (for HIV), newer antipsychotics.

Other notable subcategories related to diabetes include:

Impaired glucose tolerance: Fasting glucose less than 7mmol/L but glucose tolerance test at 2 hours is more than 7.8 and less than11.1 mmol/L.

Impaired fasting glucose: Fasting glucose between 6.1-7.0 mmol/L (cut off point is arbitrary and different in different countries.)

Impaired glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glucose often occurs before type 2 diabetes and lifestyle advice may reduce risk of progression.

Metabolic syndrome: refers to a combination of any 3 of central obesity, hypertension, hyperglycaemia and dyslipidaemia (increased triglycerides and reduced HDLs) . Metabolic syndrome is not beneficial for predicting cardiovascular risks and risk of diabetes compared to standard measures and blood glucose. However it recognises that these conditions tend to occur together and may be helpful for organising management which takes into account all these, and reminds clinicians to look for related conditions where some of these conditions present.

Presentation:

Type 1 diabetes tends to present with polydipsia, polyuria, and weight loss and may progress to diabetic ketoacidosis which may lead to reduced consciousness or coma.

Type 2 diabetes may present with general fatigue, polyuria and polydipsia over several months, visual blurring and candidal infections. Many people with type 2 diabetes are also asymptomatic and may present on routine check ups or may present with complications such as kidney disease, retinopathy or cardiovascular events. They may also present with non-ketotic hyperosmolar state.

Investigations and diagnosis:

Diabetes is diagnosed with a venous fasting glucose of over 7.0 or a random glucose of over 11.1 mmol which was defined by the WHO. 2 values are needed in asymptomatic individuals whilst one value is diagnostic in symptomatic individuals. Normal glucose levels is defined as a fasting glucose of less than 6.1mmol/L and a glucose tolerance test glucose of less than 7.8. A HbA1C (glycated haemoglobin) level of over 6.5% is also diagnostic of diabetes although a lower HbA1C does not exclude it.

Investigations for diabetes include:

- Bedside tests: Capillary blood glucose , urine dipstick for protienuria and glucosuria.

- Venous blood glucose, HbA1C levels.

- Blood tests for related conditions and complications:Full blood count, Cholesterol and triglycerides, Urea and electrolytes, liver biochemistry.

- Urine creatinine:albumin ratio and urine dipstick for microalbuminuria.

- For type 1 diabetes the presence of islet cell antibodies, anti-glutamic aside decarboxylase antibodies may help diagnosis.

- Oral glucose tolerance test for patients with borderline presentation of type 2 diabetes. (measurement of glucose after fasting and 2 hours after given 75g in 300ml of water of glucose)

Management - Type 2 diabetes

1) Structured education - should be provided to all patients at the time of diagnosis and reviewed annually. The patient and their carers are the main people managing the illness on a day to day basis, so good quality, evidence based education programmes are needed to help individuals fully understand their illness, it's long term risks and how it is managed and to empower patients to maximise their health.

2)Lifestyle advice - Lifestyle advice can help improve insulin sensitivity, reduce blood pressure and cholesterol levels, and obesity to minimise the risk of developing further cardiovascular disease.

This should include:

Dietary advice - given by dieticians in a multidisciplinary team - relevant to a patients individual needs, culture, beliefs and willingness to change and quality of life. Generally a diet with high fibre, carbohydrates with low glycaemic index, a preference for low fat dairy products and oily fish (omega 3 fats) and reduction in foods with high saturated and transfats is recommended. Food directly marketed to diabetics is discouraged.

Exercise and weight loss - aiming for 5-10% of weight loss in obese individuals.

Smoking cessation

Advice on alcohol intake and reducing the risk of hypoglycaemia, and the management of hypoglycaemia. Especially in patients on insulin secretagogues or insulin.

3)Treating hyperglycaemia - The period and extent of hyperglycaemia directly relates to the risk of micro and macro vascular complications. However, treating hyperglycaemia may also lead to multiple side effects affecting the patient's quality of life. NICE guidance therefore recommends that a target HbA1C level is agreed between the team caring for the patient and the patient, taking into account the effects on the patients quality of life, and other risks such as risk of hypoglycaemia in elderly patients prone to falling.

HbA1C levels should be treated to a minimum of 6.5% and intensive therapy to lower sugar levels more should not be pursued as the costs of the interventions and side effects to patients outweigh the benefits.

HbA1C levels should be tested between 2-6 months for any change in therapy until treatment is at a steady state and repeated every 6 months thereafter. Fructosamine estimation and quality controlled plasma glucose levels can be used in patients with blood conditions affecting HbA1C. Fingerprick testing should be used for patients on therapies with varying effect, where frequent dose adjustment is required (such as insulin) or where there is a risk of hypoglycaemia.

1) Metformin - Acts on the liver to reduce insulin resistance. Generally considered first line for both obese and individuals with normal weight.

2) Sulfonylurea- Inhibits Katp channels in B cells to stimulate insulin release. Consider sulfonylurea as first line if a patient is not overweight and cannot tolerate metformin, or if hyperglycaemic symptoms mean that a rapid response is needed. Sulfonylureas can also be added where control with metformin is inadequate. Alternatively a rapid acting insulin secretagogue can be considered for people with non routine lifestyles.

3) Dipeptidylpeptidase -4 (DPP-4) inhibitors (sitagliptin/vildagliptin) - work by stopping inactivation of GLP -1 which stimulates insulin release. Can be used if sulfonylureas are contraindicated or not tolerated due to high risk of hypoglycaemia or side effects. Should only be continued if HbA1C is reduced by 0.5% within 6 months.

Thiazolidinedione (glitazones) - Reduces insulin resistance by acting on fat and muscle cells. Can be used where sulfonylureas are contraindicated.

Alpha glucosidase inhibitor (acarbose) - works by inhibiting enzymes which break down complex carbohydrates reducing the absorption of glucose. consider for someone unable to use other oral medications.

4) Insulin - if glucose control cannot be achieved with oral hypoglycaemic agents, insulin can be added. (i.e. insulin + metformin + sulfonylurea) Alternatively exenatide (GLP-1 receptor agonist) can be added, or A DPP-4 inhibitor or thiazolidinedione can be combined with insulin.

Insulin regimes

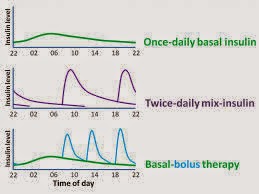

There are multiple types of insulin regimens:

Once daily regimen - usually consists of a single long acting dose of insulin given before bed, often used for type 2 diabetics converting from oral hypoglycaemics to insulin.

Twice daily regimen - Usually a combination of soluble insulin and a longer acting insulin given before breakfast and before bed. There is a higher risk of hypoglycaemia due to the overlap of long acting and short acting insulins.

Basal bolus regimen- This is where a long acting insulin is given before bed, and short acting insulin is given over meal times. This give more flexibility and is more appropriate for individuals with less regular schedules.

Insulin pumps/subcutaneous insulin infusion - An adjustable basal rate of insulin is given by a catheter from a syringe worn by the patient. Premeal boluses can be activated, and levels can be programmed according to daily fluctuations in glucose levels. This is only usually used where usual insulin regimes are not effective or in younger children where it is impractical to use regular insulin regimens.

4)Treat comorbidities such as lipids and blood pressure.

Blood pressure should be measured yearly. Treat blood pressure above 140/80 if the patient does not have end organ damage and above 130/80 in patients with renal disease, retinopathy or cerebrovascular disease. Begin with lifestyle advice, before using medical therapy. First line treatment is with ACE inhibitors unless patient is of afrocarribean descent, in which case prescribe a combination of an ACE inhibitor and calcium channel blockers or diuretic, or in women likely to be pregnant, where a calcium channel blocker should be started instead. Calcium channel blockers or diuretics should be used if control is inadequate with one drug. A combination of ACE-i, CCB and diuretic can be used if two drugs are inadequte. Finally a a-blocker, b-blocker or potassium sparing diuretic can be added if all 3 drugs are inadequate or refer to a specialist.

Start a statin in diabetics over 40 unless cardiovascular risk calculated with the UKPDS risk engine is less than 20% over 10 years. In patients already on statins, increase dose to 80mg unless cholesterol is under 4.0mmol/L and LDL is below 2.0mmol/L. Assess lipid profile 1-3 months after starting treatment and annually thereafter. Prescribe a fibrate for individuals with raised triglycerides after doing a full fasting lipid profile.

Offer low dose aspirin (75mg) to people over 50 with blood pressure below 145/90, or people under 50 with a high cardiovascular risk with type 2 diabetes.

5) Monitoring and managing complications:

Renovascular disease: Measure morning first pass urine creatinine:albumin ratios and serum creatinine and eGFR annually. Repeat twice within 3-4 months if abnormal to confirm microalbuminuria. Consider alternative causes for nephropathy. Refer to specialist under local/regional guidelines.

Perform eye screening at diagnosis and repeat annually. Arrange for urgent review by an ophthalmologist for sudden loss of vision, rubeosis iridis (neovascularisation of the iris), vitreous haemorrhage and retinal detachment. Refer to ophthalmologist if patients reach a set criteria of eye damage.

Review neuropathic symptoms annually. Use tricyclic if standard analgesics have not worked. Duloxetine, gabapentin and pregabalin should be used second line. Consider opiates if pain does not resolve and work with the local chronic pain service. Also offer psychological support.

Consider issues caused by autonomic dysfunction such as gastroparesis, erectile dysfunction, bladder disturbance, orthostatic hypotension, sweating disorders and ankle oedema. Review these issues annually and offer appropriate treatment.

Diabetics are also at increased risks of foot problems such as foot ulcers due to loss of sensation and motor nerve abnormalities caused by diabetic neuropathy. Diabetic neuropathy should be assessed annually and managed.

Type 1 diabetes

Type 1 diabetics are less likely to have other conditions increasing their cardiovascular risk. However lifestyle advice on diet, maintaining exercise and smoking cessation should be given. In addition patients with type 1 diabetes should be advised about risk of hypoglycaemia, driving and to consider using medic alert bands. Type 1 diabetes is primarily treated with insulin - usually with twice daily regimens or basal bolus regimens. General principles for monitoring complications are similar in type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

Acute complications of diabetes such as non-ketotic hyperosmolar state and diabetic ketoacidosis are not discussed in this post.

References:

Ballinger A, Patchett S, eds. Saunders pocket essentials of clinical medicine, 3rd ed.Edinburgh, Saunders, 2003.

Longmore M, Wilkinson IB, Davidson EH, Foulkes A, Mafi AR eds. Oxford handbook of clinical medicine, Oxford, Oxford university press, 2010.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), CG66, Type 2 diabetes [online] available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/11983/40803/40803.pdf [accessed: 23/04/2014]

World Health Organisation, definition and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and intermediate hyperglycaemia, [online] available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2006/9241594934_eng.pdf?ua=1, [accessed: 23/04/2014]

World Health Organisation, Use of Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) in the diagnosis f diabetes mellitus, [online] available from: http://www.who.int/diabetes/publications/report-hba1c_2011.pdf?ua=1 [accessed: 23/04/2014]

http://www.diapedia.org/management/insulin-regimens

Comments

Post a Comment